Working Hands Farm is a small org@n!c CSA farm located 17.4 miles outside of Portland, Oregon. We utilize a variety of different environmentally friendly farming methods such as, cover cropping, integrated pest management, inter-planting, composting, etc… We believe that it is essential to feed our community safe and nutritious fruits & vegetables. Our farm specializes in growing European varietals that should inspire new gastronomic adventures in all of the households we feed. Working Hands Farm was started in 2010 by Brian and Jamie, a young Portland couple with the goal of bringing a new perspective to our urban farming community. We invite you all out to the farm to come see and experience how we are doing things differently. Bring a nice bottle of wine, a blanket and something to snack on and enjoy the beauty of our garden.

Jamie is currently in Indiana collecting her parents and moving them to Portland. I would like to be the first to welcome them to their new home. Jamie’s parents originally moved from Santa Barbara to Indiana to take care of a sick family member. They have lived away from the West Coast for far to long and I wish them a safe journey home, home to the land of lush forests, breathtaking mountains and unbeatable beaches. Welcome!

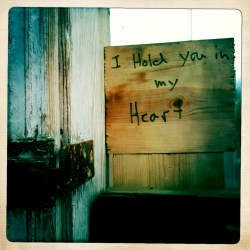

Jamie my love, although you weren’t here to start the farm with me, you have never left my side. You have sacrificed and supported me all the way with our little farm dream and I can’t thank you enough. It is in your absence that I am reminded of just how much you contribute to Working Hands Farm. I couldn’t do it without you by my side. We live this dream together and although it is not easy, we walk together, hand in hand pushing forward into the unknown. “I hold you in my Heart”

yours truly,

Brian D. Martin

What is a CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture)?

In basic terms, CSA consists of a community of individuals who pledge support to a farm operation so that the farmland becomes, either legally or spiritually, the community’s farm, with the growers and consumers providing mutual support and sharing the risks and benefits of food production. Typically, members or “share-holders” of the farm or garden pledge in advance to cover the anticipated costs of the farm operation and farmer’s salary. In return, they receive shares in the farm’s bounty throughout the growing season, as well as satisfaction gained from reconnecting to the land and participating directly in food production.

-Suzanne DeMuth, An EXCERPT from Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): An Annotated Bibliography and Resource Guide.impl

In simpler terms,

CSA is a way for us to be able to grow healthy food for our community, while ensuring that we can also earn a living wage and maintain healthy soil for generations to come. We aim to work together with our members to grow and distribute high-quality, organic produce full of the vital nutrients and minerals we need to live rich, full lives.

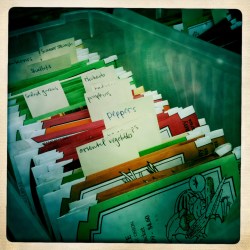

We have begun to grow a variety of what we call house vegetables. Vegetables, such as: peppers, tomatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, onions, lettuce, carrots, garlic, mustard greens, arugula, mesculin, fresh herbs, etc… We also plan on specializing in both heirloom, and unique European varietals. With time, as well as with feedback from our members, we also hope to work with other farmers to provide fresh eggs, meat, flowers, and honey. We hope to be able to surprise and delight you, and share in our bounty with you.

We are offering shares for an 18-week season, starting June 15th and continuing to November 2nd. One share feeds 2-3 people and costs $603. That breaks down to about $11.16 per week per person. If you are an individual and one share is too big for you, we encourage you to split a box with friends, family, co-workers or neighbors. Please contact us via email to register. workinghandsfarm@gmail.com

Cheers,

Brian and James

TWO WINTERS AGO there was snow on the ground in Portland—Snowpocalypse!!! We laughed at all the hyperbole, and took a couple days off work.

Over the hill in North Plains, however, a couple of farmers wereactually experiencing something like the devastation our weathermen so often invent (and milk) that time of year. Pumpkin Ridge Gardens, a small family farm, was buried under several feet of snow and ice. Their hoop houses (plastic-roofed greenhouses built over flexible piping) collapsed under the weight, and with it, so did their ability to grow any vegetables until the spring.

Pumpkin Ridge operates a year-round CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture), a subscription-based service in which customers pay at the beginning of the season for a weekly allotment of produce. James Just and Polly Gottesman started the farm in 1990 after reading about Japanese housewives that banded together to buy a farm’s entire production. It sounded like a good sustainable model for a small-scale farm. Their first year, Pumpkin Ridge sold four shares.

By the winter of 2009, Just and Gottesman were feeding 170 families. But without the hoop houses, they’d have no way to fill the weekly boxes. “The members are understanding,” Just says. “They know they’re shouldering some of the risk, and know what they’ve signed on for.” That’s been the business model ever since CSAs began catching on in the states 20-some years ago. In an age of industrialized food production, engineered produce, and monolithic corporate farms, that connection to the land, the elements, and the people who grow your food is part of the appeal.

That winter, Just and Gottesman put out word to their members, and soon they had 30 or 40 sets of hands out on the farm helping with the repairs and construction. They were able to salvage the season and thrive in the spring. But even when times are good, it’s not uncommon to see members volunteering on the farm.

That enthusiasm has helped CSAs grow exponentially in the US over the last 20 years, from a few dozen to over 4,000. Members pay a lump sum, and each week they pick up their box of produce at a designated drop site (though some farms offer home delivery). Your box will vary from week to week, depending on what’s in season and what’s growing well.

For instance, had you picked up an August box from Wealth Underground Farm last year, you’d be eating tomatoes, summer squash, cucumbers, beans, a salad mix, a head of lettuce, torpedo onions, swiss chard, hot peppers, and more. Two months later, your box would look very different—more carrots, potatoes, and turnips. (If you’re worried you don’t know what to do with those particular vegetables, Wealth Underground’s proprietors, Nolan Calisch and Chris Seigel, offer box-specific recipes on their website).

Brian Martin started Working Hands Farm last year, selling his produce at farmers’ markets and building a subscriber-base at a local architecture firm. The CSA model has been especially important, he says, because it keeps him from having to borrow large sums of money at the beginning of the season, for seeds, compost, and inevitable repairs. It allows him to budget accordingly, and do a little extra for his members. He likes to surprise customers with fresh-roasted coffee, local honey, and cut flowers from his farm.

It’s important to find a CSA that fits your needs (consider price, the range of fruits and vegetables, and the drop-off locations), and there are many in the area to choose from.Localharvest.com is a great resource, and we’ll be running mini-profiles/Q&As all week on Blogtown at portlandmercury.com, but here are a few safe bets:

Pumpkin Ridge Gardens

Length of Season: year round

Size: 80 full shares, 90 half shares

Cost: $1,390 full share/$855 half share (52 weeks)

Highlights: purple sprouting broccoli, arugula, purple tomatoes

Wealth Underground Farm

(wealthunderground.blogspot.com)

Length of Season: June-November

Size: 30 shares

Cost: $600 (25 weeks)

Highlights: Hakurei turnips, a special mix of salad greens

Working Hands Farm

Length of Season: June-November

Size: 50 shares

Cost: $603 (21 weeks)

Highlights: kohlrobi, sun gold tomatoes

Tyler and Alicia Jones on their farm in Corvallis, Ore. More Photos »

By ISOLDE RAFTERY

Published: March 5, 2011z

CORVALLIS, Ore. — For years, Tyler Jones, a livestock farmer here, avoided telling his grandfather how disillusioned he had become with industrial farming.

After all, his grandfather had worked closely with Earl L. Butz, the former federal secretary of agriculture who was known for saying, “Get big or get out.”

But several weeks before his grandfather died, Mr. Jones broached the subject. His grandfather surprised him. “You have to fix what Earl and I messed up,” Mr. Jones said his grandfather told him.

Now, Mr. Jones, 30, and his wife, Alicia, 27, are among an emerging group of people in their 20s and 30s who have chosen farming as a career. Many shun industrial, mechanized farming and list punk rock, Karl Marx and the food journalist Michael Pollan as their influences. The Joneses say they and their peers are succeeding because of Oregon’s farmer-foodie culture, which demands grass-fed and pasture-raised meats.

“People want to connect more than they can at their grocery store,” Ms. Jones said. “We had a couple who came down from Portland and asked if they could collect their own eggs. We said, ‘O.K., sure.’ They want to trust their producer, because there’s so little trust in food these days.”

Garry Stephenson, coordinator of the Small Farms Program at Oregon State University, said he had not seen so much interest among young people in decades. “It’s kind of exciting,” Mr. Stephenson said. “They’re young, they’re energetic and idealist, and they’re willing to make the sacrifices.”

Though the number of young farmers is increasing, the average age of farmers nationwide continues to creep toward 60, according to the 2007 Census of Agriculture. That census, administered by the Department of Agriculture, found that farmers over 55 own more than half of the country’s farmland.

In response, the 2008 Farm Bill included a program for new farmers and ranchers. Last year, the department distributed $18 million to educate young growers across the country.

Tom Vilsack, the secretary of agriculture, said he hoped some beginning farmers would graduate to midsize and large farms as older farmers retired. “I think there needs to be more work in this area,” he said. “It’s great to invest $18 million to reach out to several thousand to get them interested, but the need here is pretty significant. We need to be even more creative than we’ve been to create strategies so that young people can access operations of all sizes.”

The problem, the young farmers say, is access to land and money to buy equipment. Many new to farming also struggle with the basics.

In Eugene, Ore., Kasey White and Jeff Broadie of Lonesome Whistle Farm are finishing their third season of cultivating heirloom beans with names like Calypso, Jacob’s Cattle and Dutch Ballet.

They have been lauded — and even consulted — by older farmers nearby for figuring out how to grow beans in a valley dominated by grass seed farmers.

But finding mentors has been difficult. There is a knowledge gap that has been referred to as “the lost generation” — people their parents’ age may farm but do not know how to grow food. The grandparent generation is no longer around to teach them.

So Ms. White and Mr. Broadie turned to YouTube for farming tips. They scoured the antiques section of Craigslist for small-scale farming equipment.

“When we started, we didn’t even know what we needed,” said Ms. White, 35. “We found out that a tractor built in the 1950s would drive over our beds and weed them.”

She said that they farmed because they felt like part of a broader movement, but that the farmer’s life was not always romantic. Last year, their garlic crop rotted in the ground. Mr. Broadie, 36, is unable to repay his student loans. They do not have health insurance, or know when they will be able to afford to buy land.

On a recent Saturday, Ms. White and Mr. Broadie moved to a farm owned by a couple that wants to support local agriculture. They hope it is their last stop.

That evening in Corvallis, the Joneses prepared for a party at Mary’s River Grange Hall with friends.

Among them, Jenni and Scott Timms, both 28, had quit their engineering jobs in Houston the month before. They would like to own their own farm someday.

“We see people like Tyler and Alicia doing it, and we thought, ‘If they can do it, so can we,’ ” Mr. Timms said.

The Timmses had arrived at the Joneses’ 106-acre farm the day before and were staying in a run-down Victorian house on the property. As they waited for their hosts, they sipped a microbrew in a kitchen overlooking wooded farmland. They said they were drawn by the state’s beauty and its 120 farmers’ markets.

And it seemed that other beginning farmers in Oregon shared their values. At the Grange hall later that evening, the gravel lot was lined with Subarus with bumper stickers that read “Buy locally,” “Who’s Your Farmer?” and “Let’s Get Dirty.” One farmer arrived by bicycle.

Inside, women in woolen sweaters and hats danced to the music of a bluegrass band. There was no formal speech, just the Grange master’s yell that food was ready.

The Grange master, Hank Keogh, is a 26-year-old who, with his multiple piercings and severe sideburns, looks more indie rock star than seed farmer. Mr. Keogh took over the Grange two years ago.

He increased membership by signing up dozens of young farmers and others in the region. He had the floorboards refinished, introduced weekly yoga classes and reduced the average age of Grange members to 35 from 65.

The young farmers crowded around a table brimming with food they had produced — delicata squash, beet salad, potato leek soup and sparkling mead. On a separate table were two pony kegs of India pale ale.

It was the first time the Joneses had been to the Grange, and Ms. Jones said they would probably join. She had already told the mead makers that she would connect them with Portland restaurants that wanted local honey.

“Literally, four years ago, this was not happening,” Ms. Jones said, gesturing to the 30 farmers who congregated at the hall. “Now, everywhere you turn, someone’s a farmer.”

James and I returned home from Haiti more than two weeks ago. It feels good to be back in Portland, to be back in our home. It’s that view that always brings me back and swaddles me in homeishness. You know the one, as you head south on I-5 and you pass over the Willamate. You look down at Portland below with its lights, warm… and their reflections dancing in the water. That’s the view that lets me know I have returned to the town I was born in. To the town I was born to live in. After a week of snow and rain and coffee and beer and sweat pants and Netflix’s finest we decide it is time to get back to the farm. and wow what a mess…

But what fun to clean and organize, to wake our farm from its slumber. I imagine many of you know what it is like to dive into a project and never look back. How it no longer becomes work but a personnel vendetta to rearrange the furniture in a cluttered space or perhaps preparing a perfect meal just for yourself. I love the delightful refuge of simple meditative tasks. Season number two here we come… Dirty hands, Clean Hearts.

Yours truly,

Brian

first day back to the farm for the season and the mood was silly. brian and i were both very excited to be back… breathing fresh air, marveling at our kale trees (pictured in the background of the photo above), listening to music, and working at our own paces. i hadn’t realized how much i missed the pace of the farm until brian would come bounding out of the greenhouse to share his latest brilliant idea, or i would get completely absorbed in the silence of my current project. i had ample time yesterday to reflect on the start of our second year on the farm and how it compared to where we were at this time last year.

last year at this time we were planting our very first seedlings. this year we plant with the confidence born of a year’s worth of hard work, mistakes, and small triumphs. i look forward to the year ahead for us and our growing community of friends and family who are as excited as we are about the new year.

best,

james

It is a short film that depicts another side of Haiti, a collection of short clips of Haitians that are happy. Enjoy.

I thought I would lighten the mood a bit and post a video that I think gives a very accurate portrayal of life on the farm. It shows with deep sincerity the ways in which we toil to bring life into our soils and reveals subtle magic of the true farm experience. p.s. This video is for mature audiences only.

This is a picture that I took today on my way to buy beans and rice in the market. It is a day before the official 2nd round election announcement is made and the MINUSAH (United Nation stabilization Mission in Haiti) has been making its presence known. Tomorrow will be an important day for Haiti and we patiently await the outcome.

yours truly, Working Hands Farm

This is a set of photos of one of the 24 schools in Port-Au-Prince that ILF is weaning off of a charcoal dependency. We began distributing large briquette (made of paper waste and sawdust) burning stoves to schools last may we are still going strong. By the end of February we will have distributed over 100 stoves and trained as many school cooks. Here are some photos of the schools we work in. To learn more about Lifeline click here.

Hello friends,

Today I have decided to make a post of a post, or rather a post of a blog. This is a blog that Jamie and I have been following for a while now and it never ceases to amaze and inspire. It is extremely well written and the pictures are as incredible as the stories they tell. I hope you take the time to check it out, it is called “On the Goat Path.”

yours truly , Working Hands Farm

This is a short film that I put together to mark one year after the earthquake in Haiti. It is a montage of images from my daily life here. Much of the footage comes from my commute to work, distribution days in the IDP (Internally Displaced Peoples) camps and my favorite hikes in the mountains. All of the images you see were taken within one week of the one year anniversary of the earthquake. I hope you enjoy the film. If you like it please share it with others.

here is another visual morsel to tickle you today. it was made by partners in health (‘zanmi lasante’ in kreyol), an organization started in haiti in 1985 to provide access to healthcare to poor, rural haitians. it has since expanded to several other countries worldwide. here in haiti, it has also expanded to include agricultural program, called ‘zanmi agrikol’. this program excites me greatly. and although i am not in accord with their use of chemical sprays, this program helps empower haitians through education, seed-sharing, and community-building. after spending months witnessing (and decades reading about) aid organizations perpetuating a culture of dependency (haiti has become known as the ‘republic of ngos’), zanmi agrikol is an inspiration for those of us who hope to see haiti become a thriving, independent nation.

We thought that you guys would enjoy this. It is a film that some good friends of ours at Juliet Zulu produced last spring. Our Jamie from Working Hands Farm stars in it and we are very proud to say so. We love the work that Juliet Zulu is doing in Portland, it makes us fall in love with our fair city time and time again. We encourage you to check out their website, http://www.julietzulu.us/

A YEAR AND A DAY

by Edwidge DanticatJANUARY 17, 2011

n the Haitian vodou tradition, it is believed by some that the souls of the newly dead slip into rivers and streams and remain there, under the water, for a year and a day. Then, lured by ritual prayer and song, the souls emerge from the water and the spirits are reborn. These reincarnated spirits go on to occupy trees, and, if you listen closely, you may hear their hushed whispers in the wind. The spirits can also hover over mountain ranges, or in grottoes, or caves, where familiar voices echo our own when we call out their names. The year-and-a-day commemoration is seen, in families that believe in it and practice it, as a tremendous obligation, an honorable duty, in part because it assures a transcendental continuity of the kind that has kept us Haitians, no matter where we live, linked to our ancestors for generations.

By this interpretation of death, one of many in Haiti, more than two hundred thousand souls went anba dlo—under the water—after the earthquake last January 12th. Their bodies, however, were elsewhere. Many were never removed from the rubble of their homes, schools, offices, churches, or beauty parlors. Many were picked up by earthmovers on roadsides and dumped into mass graves. Many were burned, like kindling, in bonfires, for fear that they might infect the living.

“In Haiti, people never really die,” my grandmothers said when I was a child, which seemed strange, because in Haiti people were always dying. They died in disasters both natural and man-made. They died from political violence. They died of infections that would have been easily treated elsewhere. They even died of chagrin, of broken hearts. But what I didn’t fully understand was that in Haiti people’s spirits never really die. This has been proved true in the stories we have seen and read during the past year, of boundless suffering endured with grace and dignity: mothers have spent nights standing knee-deep in mud, cradling their babies in their arms, while rain pounded the tarpaulin above their heads; amputees have learned to walk, and even dance, on their new prostheses within hours of getting them; rape victims have created organizations to protect other rape victims; people have tried, in any way they could, to reclaim a shadow of their past lives.

My grandmothers were also talking about souls, which never really die, even when the visual and verbal manifestations of their transition—the tombstones and mausoleums, the elaborate wakes and church services, the desounen prayers that encourage the body to surrender the spirit, the mourning rituals of all religions—become a luxury, like so much else in Haiti, like a home, like bread, like clean water.

In the year since the earthquake, Haiti has lost some thirty-five hundred people to cholera, an epidemic that is born out of water. The epidemic could potentially take more lives than the earthquake itself. And with the contagion of cholera comes a stigma that follows one even in death. People cannot touch a loved one who has died of cholera. No ritual bath is possible, no last dressing of the body. There are only more mass graves.

A year ago, watching the crumbled buildings and crushed bodies that were shown around the clock on American television, I thought that I was witnessing the darkest moment in the history of the country where I was born and where most of my family members still live. Then I heard one of the survivors say, either on radio or on television, that during the earthquake it was as if the earth had become liquid, like water. That’s when I began to imagine them, all these thousands and thousands of souls, slipping into the country’s rivers and streams, then waiting out their year and a day before reëmerging and reclaiming their places among us. And, briefly, I was hopeful.

My hope came not only from the possibility of their and our communal rebirth but from the extra day that would follow the close of what has certainly been a terrible year. That extra day guarantees nothing, except that it will lead us into the following year, and the one after that, and the one after that. ♦

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2011/01/17/110117taco_talk_danticat#ixzz1B77E05IU